At the G7 and G20 summits, Trudeau and Macri will be facing the challenge of upholding openness and multilateralism in the face of their big US neighbour, too. The G7, BRICS and G20 summits in 2018 will also be crucial to the success of the United Nations’ (UN) summit in 2019 on implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This agenda was adopted in 2015 by all heads of state and of government of the world as a plan for people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership.

The beginnings of today’s summit processes date back to the 1970s with the formation of the G7 by the large western countries, later – with the temporary inclusion of Russia – the G8. The global economic crisis that began in 2007 led to the formation of the G20 on the level of Heads of State and Government with the inclusion of emerging powers. The BRICS group has held summits since 2009, although South Africa just joined this group in 2010. Significant political capital is invested in the parallel summit processes with their intersecting priorities; this investment should be one of benefit to humanity and the planet. The G20 see themselves as the premier forum for their international economic cooperation. The G7, declared almost defunct after the first G20 meetings, is now understanding their role – despite many a disagreement – to be that of a leading community of shared values. The BRICS group with its variety of social systems and the particular weight of China, aims above all to achieve closer cooperation between the economies and societies of its members. G7 and BRICS sometimes refer to the G20, but feel that they are processes of their own. All groups embrace a scope of topics far beyond economic questions alone. In view of the composition and global weight of the G20, G7 and BRICS, it is obvious that the goals and targets of Agenda 2030 can only be achieved if they are also vigorously pursued and put into practice through these groups and in the respective member countries.

A Good Start in 2016

In the year following the adoption of the 2030 Agenda, the G7, BRICS and G20 summits in 2016 gave their clear avowals of their intentions to implement the Agenda nationally as well as internationally. For the Japanese presidency, this Agenda was then one of their priorities. At their summit in May, the G7 member countries undertook both the implementation of the Agenda in their own countries and the promotion of it internationally, and explicitly positioned many of their initiatives in relation to the Agenda. At the G20 summit in September, chaired by China, the 2030 Agenda was greatly bolstered by the adoption of a G20 Action Plan. This plan underlines the universality of the Agenda and documents in an annex the first national and international implementation steps by every single member of the G20. In October 2016, the BRICS countries’ summit under India’s chairmanship committed to “lead by example” and take “bold transformative steps” to implement the G20 Action Plan.

In the wake of such determination, it was incumbent on the presidencies of the following year to follow up words with actions – particularly, in the context of the G7 and G20, with a view to the new US administration. The Italian G7 summit in May 2017 was not able to sustain the previous year’s ambition, mentioning the 2030 Agenda as if in passing, and only establishing a connection to it on the subject of Africa. In contrast, the German G20 summit in July was successful in confirming the 2030 commitment with its Hamburg Update of the G20 Action Plan, concluding several G20 initiatives with explicit reference to the Agenda. In the Summit Declaration, the G20 countries recognised the Agenda as a milestone towards global sustainable development and undertook to align their domestic and international activities with it. The Chinese BRICS summit of the following September also renewed the obligation to fully implement the 2030 Agenda and placed the BRICS dialogue with emerging and developing countries within the same framework.

It is worth noting that the G20 and BRICS are clearly supportive of the UN-led audit of the 2030 Agenda. With the exception of Russia, the United Kingdom and the US, all the members of the three groups have already submitted the relevant Voluntary National Reviews to the UN or advised them to be available by 2019. However, only the G20 has a process for monitoring national and collective implementation of the Agenda through progress reports and mutual learning. G7 and BRICS continue their tendency to see the Agenda in the light of established North- South or South-South reasoning, rather than promoting its fulfilment at home, too. Not one of the three groups outlines the extent to which their initiatives contribute to the quantified, time-bound goals of the Agenda, nor do they say what financial means they are allocating to these goals at home and globally.

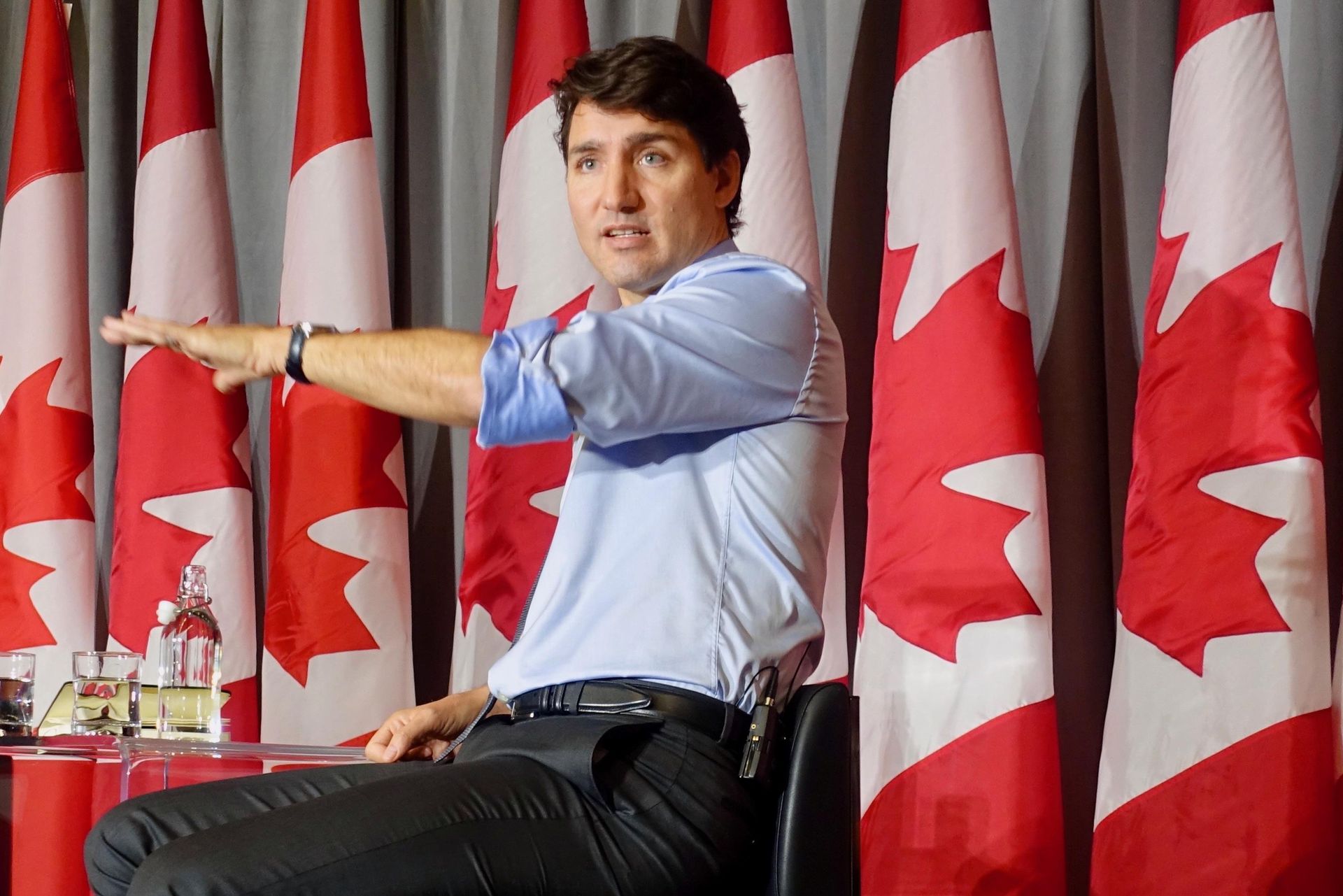

Can Macri forge a Team 2030 together with Trudeau and Ramaphosa?

Argentina’s overarching theme of Building Consensus for Fair and Sustainable Development aims to maintain the leading role of the G20 with respect to the 2030 Agenda. This could lead to an attractive Buenos Aires Update of the G20 Action Plan. The national implementation of the Agenda by Argentina should be reason enough to include the implementation steps of each of the G20 countries in the Update. The Canadian G7 and South African BRICS presidencies have not as yet made explicit reference to the Agenda in their central themes. With the Future of Work and Industry 4.0, all three presidencies have prioritised a common social challenge as priority, although this urgently needs to be correlated with the 2030 Agenda. All three presidencies also emphasise global public goods like peace (G7, BRICS), climate and oceans (G7), soils (G20) and vaccines (BRICS), but concrete measures have until now failed to meet expectations. If the G20, G7 and BRICS wish to contribute to the success of the next UN summit on the 2030 Agenda, the timetable would suggest that the three groups must achieve considerably more in 2018.

Trudeau, Ramaphosa and Macri must show their enthusiasm for reform on an international level, too, and address the task in a determined frame of mind. As the G20 presiding country and one that is not also a member of the G7 or BRICS, Argentina might invite Canada and South Africa to jointly share clear steps towards implementation of the 2030 Agenda. Initiatives would have to clarify in quantitative terms what they would contribute to the attainment of Agenda goals and targets including global public goods, and what additional efforts are needed. G7 and BRICS should make the domestic implementation of the Agenda the object of their summit deliberations and cooperation. In Buenos Aires, the G20 should be presenting a report on their implementation of the 2030 Agenda, and this then should become part of the preparations for the UN Summit in 2019. On this basis, the presidencies of the G20 (Japan), G7 (France) and BRICS (Brazil) in 2019 will have to show what valuable contributions these groups are making to an Agenda decided at the UN.

About the Authors:

Adolf Kloke-Lesch is the Executive Director of the German Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN Germany).

Janina Sturm is a Researcher with the German Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN Germany).

The German Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN Germany) is part of the global SDSN and was founded in April 2014 by leading German knowledge centres. The network pools knowledge, experience and capacities of German academic, corporate and civil society organisations in order to contribute to the sustainable development of Germany as well as to German efforts for sustainable development across the globe.